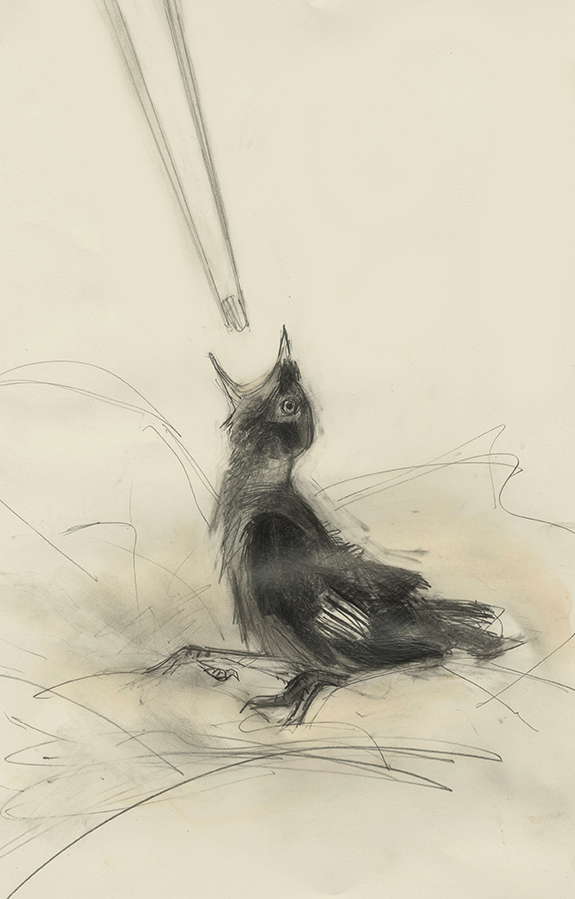

This is Jack as I first knew him

We first met each other in early May. Jack had tumbled from one of the dovecotes that line the eves of an old stone barn where a clattering of daws nest in the Spring. He was tucked in a pocket of long grass yelling “Chyak Chyak” in a clear high pitched voice. It would have been only a matter of time before a passing cat would have had him for lunch. These encounters with fledgeling daws happen every year, usually I fetch a ladder and place the young birds back into the nests from where they have tumbled, but on this occasion a colony of bees had arrived and made their home in the next door cote. Rather than risk getting stung I took the half naked, semi feathered creature into the house and gave it to Mami to look after. We fed him with tinned cat food from chop sticks and then put him on a bed of soft toilet tissue on the floor of a rusty old budgie cage.

In olden times they were called daws, just why they added the Jack prefix is unknown. Sometimes Jack is added as a prefix to mean maleness, as in Jack Ass, but Jack also can mean small as in Jack Snipe. Jackdaws are amongst the smallest members of the crow family, so its name small crow is very appropriate. Another compelling theory is that their call Chyak Chyak sounds like Jack Jack.

Jack looked like ET with vivid blue eyes and acted like a clockwork toy. He spent all day sleeping until something passing would make a noise and wake him up, then his head would stick up and he would start yelling Chyak Chyak with all his might until we had fed him more cat food. When he was finished eating he would reward us with a poo before collapsing back into a heap.

Corvids, as crows are known, are sometimes called “feathered Apes” because they are so intelligent. I recommend you look at this remarkable video of a crow using his mind to solve a problem of how to use a piece of wire to pull a basket of food from the bottom of a deep glass jar. As Jack grew he changed from behaving like a clockwork toy into a super intelligent, social and emotional being.

In those first few days he grew very fast, and after a week he walking about the cage and trying to get out. It was about this time that something more subtle emerged. I would see him enjoying great long extended stretches of his wings and he would hiss if I annoyed him: the clockwork toy was developing spirit.

He obviously did not like the confinement of the budgie cage and so we bought a very expensive very large dog cage. It did not work, a few days later he was clambering to escape from that that too and we had to give him a whole room where he could fly and play with visitors.

I have been very interested in the mind for some time. When I am drawing people relaxing by the sea I have noticed that all the children share a fascination of stones….they collect stones and put them into piles and throw them in the sea……and the adults retain the same interest. If Jackdaws went to the sea-side, and you will sometimes see daws there, they would spend all their days looking for objects to break.

They break things they use their beaks and their hands

every new object is checked out for its break-ability.

His beak was sharp, pointed, shiny, vicious, delicate and super-sensitive to the outside world. Jack explored and experienced the world through his beak.

With extreme precision he would hammer like a woodpecker on to the very tip of a chopstick, never missing his aim, until the wood splintered…and afterwards he knew his chopstick. When I held his chopstick close to him he would snatch it away from my hands. Sometimes a tug of war would develop.

and after he owned it again he would take it away in his beak

He was always inquisitive. When I came into the room he picked my pockets, and if I had a hand behind my back he would peer round my waist to check that I was not hiding something from him. New objects were always fully investigated

and shared

and if I left them in the room they would be broken by the time I returned. Jack was not completely self-centred; sometimes he would help with the clearing up by collecting the broken pieces and putting them in a pile on the shelf.

Jack was also sensual. I have often noticed how our cats enjoy new sheets on the bed and fresh water.. Jack was pretty picky too, his sensual experiences were highly developed; he would eat only the chunks of cat food and leave the jelly. One day when visiting Jack I had an apple in my hand, and Jack looked at what I was eating with envious eyes so I gave a piece. He took it gently in his beak, and I could see his tongue caressing and licking the juice to find out if it was tasty, then he swallowed it. 30 seconds later he spat it out again. Jack had decided he did not like apples!

He loved helping me when I changed the dirty newspaper for new and brought a bowl of fresh water everyday which was a “must have”.

One day I discovered the reason why his bowl of water got so dirty, he was using it as a bath.

After I understood his need I brought him a larger bowl for his ablutions. He understood it purpose at once and jumped right in, splashing about vigorously making everything around him wet. I was standing some yards away with my back to the wall and I still got soaked.

He got out of his bath looking like a porcupine, and shook himself like a dog

and preened his feathers.

After baths he looked he looked sleek and beautiful.

Jack had an intelligent mind that needed to be engaged. He liked my

visits but really did not like it when I did not want to play. When I

was drawing he would always take a look at my pencil box. After a while

he learnt what he was looking for; his first priority was to take out

the rubbers and pieces of chalk because he knew they would break if he

thumped them hard enough with his beak, and he also knew I would chase

him to get them back.

His next priority were the plastic propelling pencils because he liked to pull out the rubbers and break the lead tips.

After emptying my pencil box he would arrive on top of my sketch board

and would crawl, slip and tumble down the paper never taking his gaze away from the tip of my pencil

which he would launch himself at, breaking the fine lead tips with a single snip using the end of his beak with a delicate finesse. Other times, perhaps when I was using a piece of graphite, he would grasp the stick with his beak and not let go. His head would sway back and forth across the paper as I scribbled from side to side

sometimes his attacks were launched from my sleeve

After all his efforts to stop me drawing had failed he would start ripping the paper I was drawing on. Jack was a real attention seeker.

When he gained my attention he would sometimes calm down. He loved to sit on my shoulder and look out of the window with me, or cuddle up on my arm and make soft intimate sounds of affection. On these occasions he used his beak with a lot of gentleness, perhaps nibbling and preening what is left of my hair. He liked to push his beak to my mouth, like you see birds do sometimes, but if I smiled he would jab at my teeth because he thought them interesting shiny objects that needed to be tested for their breakability.

We found Jack in May. The internet told us that if we released him too early he would get bullied by other birds, so we waited until August to release him. On his last day of captivity Mami and I visited him in his room, he clambered all over Mami, as he always did

and stood on her head, as he always did

We took some hurried photos with an iphone, none were very good. This is a last memory of Mami with Jack

Instead of giving him his morning meal we opened the window wide and went downstairs to call him. We could see him flying around the room, sometimes he looked at us before retreating back inside. I went upstairs and Jack came straight to my arm. Together we looked out of the open window and at Mami below who was calling him to a bowl of food. Jack looked and spread his wings and flew. His flight was unsteady, he scooped in the air and went behind some trees. We never saw him again.

What I have told you about our adventures with Jack is only a flavour of what happened. There is so much more that I never achieved to show in my drawing. I think he got lost, I do not think he really wanted to leave.

..and that is the end of my story of a tame jackdaw. Everyday I go out and call him, but he has never shown himself. At this time of year food is plentiful, he knows how to feed himself. He used to catch flies in his room. I think he is OK.