Introduction to Northern Ballet

I saw my first ballet soon after moving to London in about 1972. In those early years I saw many legendary dancers including Margot Fonteyn, Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova, Ekaterina Maximova and Gelsey Kirkland. The Royal Ballet itself was going through a golden period with world famous choreographers and dancers. Kenneth MacMillan was their resident choreographer, and he had taken over from the great Frederick Ashton who had set a British style and was still working. These two choreographers introduced a new subtlety to emotional storytelling that rocked the world of classical ballet. London ballet had its own great dancers, we (Mami and I) even went to the farewell performance of the great partnership between Anthony Dowell and Antoinette Sibley. The London ballet scene was world class and booming.

In those days there was limited crossover between classical and contemporary dance. Young dancers were encouraged to chose either classical or contemporary style. In contemporary world London had smaller companies like the Ballet Rambert and a theatre school at “the Place” that put on esoteric performances for very niche followings. In the US Martha Graham had introduced new schools of movement and ways of dancing. New York’s choreographer George Balanchine , whose style sort of straddled the divide, would bring his company to London but we never really liked his work. Europe had it own crossover impresarios, Maurice Bejart, who brought his company France to London several times, For me Bejart’s work have retained tis vibrance better than Balanchine, in contrast the narrative ballets of Kenneth Macmillan are as vivid and relevant today as they ever were. MacMillan’s Ballets, “Romeo and Juliet” (1964) and “Manon” (1974) and the gorgeous Mayerling (1977) remain crowd pullers at the heart of British and the Royal Ballet’s identity.

In 1987 we went to see a new version of one of the great 19th century romantic classics, Don Quixote, performed by the Northern Ballet. The choreographer was Michael Pink. At the end of the performance the artistic director, Christopher Gable, came on stage and begged the audience to fund his fledgling company. The performance was not really that stunning, and I expect few of us had much inkling that we were witnessing the birth of a partnership that would carry on from where MacMillan had finished, and revitalise British Ballet.

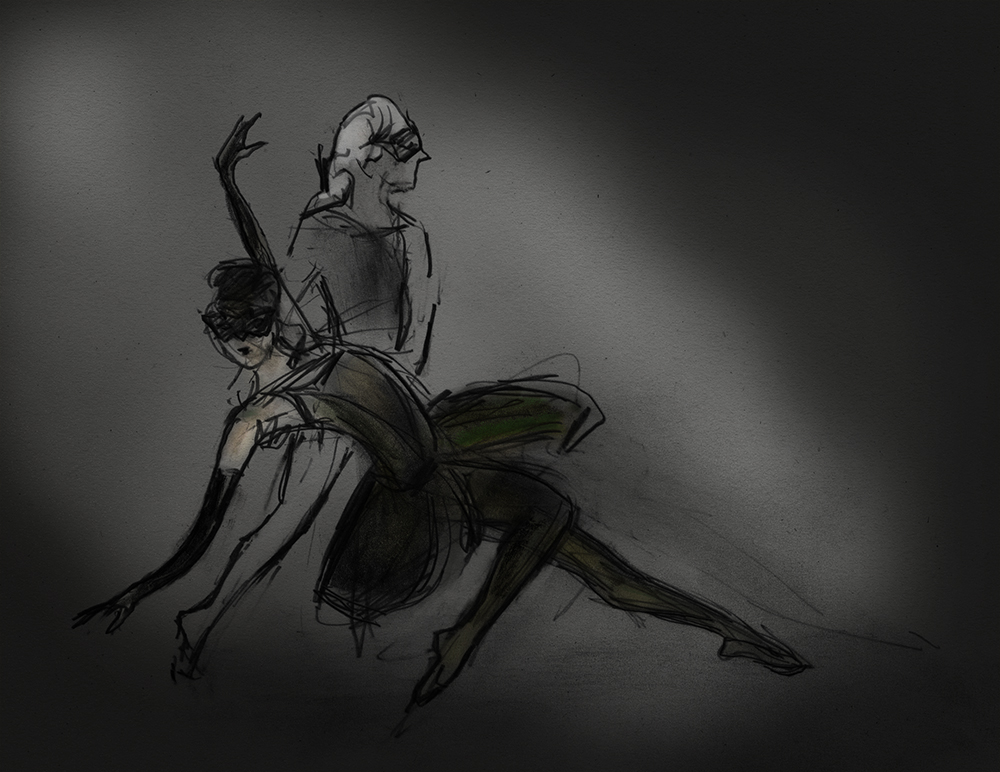

Ten year’s later, in 1996, Northern Ballet brought Dracula to Sadler’s Wells. The ballet was another collaboration between Michael Pink and Christopher Gable, with its own commissioned score by Philip Feeney. It was free of any baggage from the romantic era. The narrative was punctuated with three, or was it four?, pas de deux bewteen Dracula and his victims. Mami and I were gob-smacked at the brilliance and originality of this work which blended contemporary with classical styles. We have been avid fans of Northern Ballet ever since.

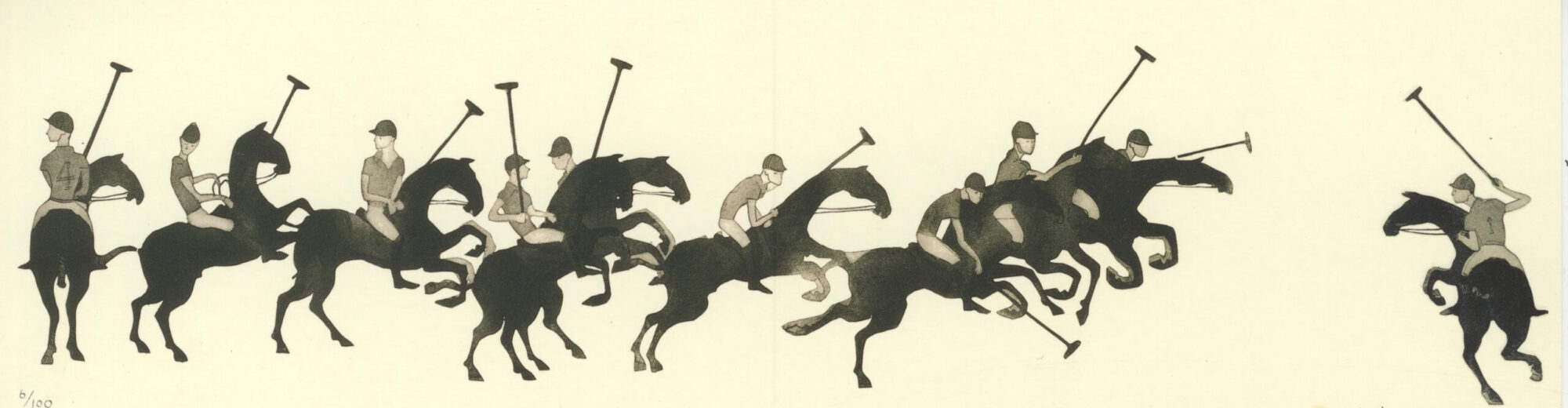

So far I have illustrated one of Northern’s productions

Casanova