Introduction

I have often heard people exclaim “I was never able to draw”, as if they have been defeated by a task that is beyond their capabilities. Often these people equate good drawing technique with owning the skills to make pictures that have the accuracy and finish of a photograph. For me good drawing technique is not about competing with a camera. In my opinion a person with limited skills, but who draws expressively and with imagination, has higher social and artistic values than a skilled draughtsman whose finished work look like polished photographs. If I want a photograph I use a camera?

“learning to draw” is about learning how to make pictures that express personal feelings. An artist who understands the rules, lets call it grammar, used by our minds to read visual information will be in control of . These rules are variants of rules that are found in other spheres of intelligence; thinking, talking to yourself and to others, seeing, music making, and socialising. When we use the word grammar, we think linguistics and language, but the word might just as well be used in almost every aspect of the mind; all thinking, the generation of images and sound inside our heads, feelings, movement are all experienced at the end of a chain of physical events starting with sensory impulses and finishing as mental sensations.

It is common knowledge that grammar which make our sentences understandable, for example a sentence like “The cat sat on the mat” makes perfect sense to an English speaker because to obeys English grammar. Without grammar the same words in a different order; “mat cat the on sat” are confusing and have a vague meaning. If we jumble up the letters as well; “tma act ats het no tma” the sentence now makes zero sense. (please note; that an element of grammar is also cultural; the grammar that works for an Amazonian Indian does not work for a Russian city dweller. It is the same with marks on paper.)

As babies we learn to speak without knowing what verbs or nouns are. Likewise we can learn to draw without learning how the processes of drawing work. As we grow up we are sent to school to learn how grammar works, and extend our vocabulary of words and concepts. Some of us become so enthralled with the pleasure of using words that we end up being highly skilled at explaining complex and sensitive thoughts and even writing poetry and plays. It is not generally appreciated that it should be the same with drawing. Whilst it is possible to develop your drawing skills by yourself through trial and error, it is also probable that knowledge of how visual grammar works will fast track your development and artistic skills to much higher and more enjoyable levels.

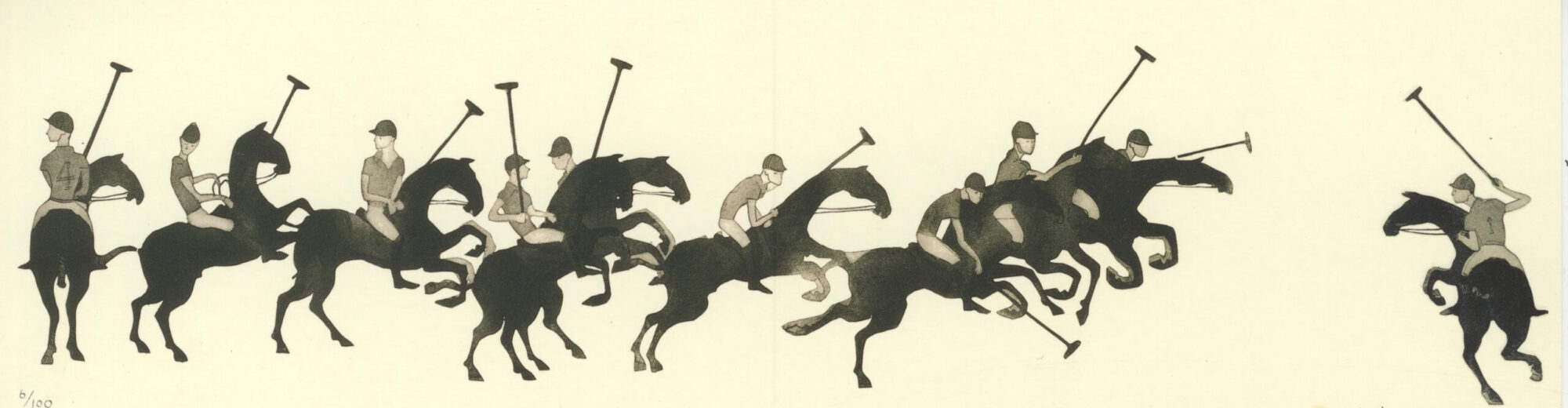

Art schools tend to teach drawing by putting a static model in front of a group of students for hours on end, and then to tell the students to carefully copy what they see. The students measure distances and copy outlines, they carefully shade areas they perceive to be darker and the results look like a very bad photograph. This method of learning to draw seems to me to be an attempt to exculpate grammar from the teaching of drawing. I did my share of drawing from posed models, and it is a useful exercise, but anyone reading my website will know most of my learning was through trying to capture form whilst the models twisted and turned in from of me.

For years I banged my head against the wall, not understanding the processes I was trying to conquer and making painfully slow progress. My method of learning suddenly speeded up after I understood drawing follows grammar. Appreciating marks in a drawing work like letters and words of a sentence was a big moment in my development. Knowing the basics of visual grammar put me in control of my learning and drawings, and enable me to express myself more accurately and concisely. I am not suggesting visual grammar will instantly transform a beginner into a Shakespeare of drawing, it is always the case that reaching high skill levels only happen after the student has spend years learning and practising how they present their ideas.

The purpose of this series of essays is to put you, the beginner, in the driving seat, and to speed up the development of your own individual style of speaking with marks. I want to provide you with some guidelines about how you can become an individual who can express feelings on paper. After that it is for you to decide what you want to express with your new language skills.

Part 1 Placement and Context

Aspects the rules of visual grammar are similar to the methods of linguistic grammar. We are familiar with how meaning of a sentence is determined by the order in which words are spoken. So the “cat sat on the mat” is different from the “mat sat on the cat”.

Drawings are constructed as an arrangement of marks, and how we read a drawing is determined by the mark is placement and relationships of the marks to each other. This led me to an obvious realisation that the same shaped mark put in one position can mean something completely different when it is moved to another position in the same drawing.

Let me