Part 1 – learning to draw the Umwelt

Introduction to Umwelt

Releasing myself from the world of words, I look up from my book. In my world of vision Zaza picks her way towards me, I can imagine her feeling of the dampness of the rotting leaves under her silent paws. She jumps up to sit next to me. I know she wants to share a moment of togetherness, although I am not sure what that means. I place a sketch book next to her and she understands my action and chooses the comfort of sitting on the book’s dry surface

Together our eyes share all that is happening in our little patch of wildness, but our experiences must be very different? I get my pleasure seeing the milky heads of Candlemas bells rising out of the cold earth to grasp the weak warmth from rays of the sunlight. A yellow light filters through a twig laced lattice high above our heads, and it reminds me of a church window. My mind wanders to thoughts of spring festivals and new life.

Zaza’s mind is elsewhere; her wet nose is pointing towards bushy ropes of ivy that hang in garlands from the trunk of an ancient cedar tree. She is so wrapped in attention that her whiskers twitch, her pricked ears are catching every last sound of movement in amongst the leaves. We are both watching a wren fidgeting in patches of darkness, and the wren is watching us back. He is agitated and hostile, and from his bunker fires volleys of chattering abuse. His hostility awakens the attention of blue and great tits that flit on the branches surrounding our spot, and high on the old cedar the black beaked jackdaws start cracking the air with a raucous chatter. We are living at the centre of a parliament of noise and admonishment.

After a while Zaza is bored by the birds, or she has another idea, I don’t know what? She jumps down and meanders her curved body between the smells of sleeping brambles and the remnants of last autumn’s lush vegetation. She slinks out of my world. I look back down to my book. Words tumble into my mind. Soon the memories of Zaza, brambles and birds are overwhelmed into a wall of new thoughts, and my world is far away from the spot I am sitting.

Well that is my story…….. were you to ask Zaza what happened she would tell you she experienced something quite different. That is if Zaza could speak, which she cannot. She does not know my world of words and grammar, and she will not think of festivals when she sees snowdrops, or churches when she sees twig-laced light. Like us she feels the dampness of the leaves under her bare feet, but we have no whiskers to measure the air. We feel we know each other because our perceptions overlap, but our worlds are so different. I do not think it is as bad as Ludwig Wittgenstein, the Austrian philosopher, said, “If a lion could talk, we would never understand him.”. I believe a level of understanding between us exists.

Subjective Experience and Umwelts

The two most extraordinary mysteries in the universe are Consciousness (he subjective experience we know we have) and the Brain’s management of Consciousness. There is a phrase commonly used amongst cognitive scientists to describe subjective experience, it is “there is something that it is like to be“.

For their survival Nature has incorporated an appropriate set of tools for perception for the bodies of each species, consequently each species experiences subjectivity differently. We call the perceptual tool kits Umwelts, and they are as important and individual a feature in the design of our bodies as are our legs or hands. For instance a kangaroo has big back feet because it needs big feet, so it is also for our umwelts; dog have long sensitive noses because they need them for hunting.

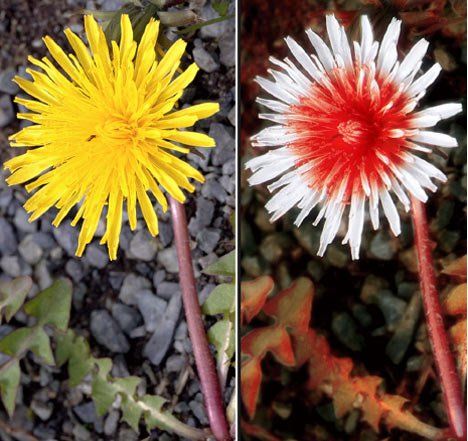

Bees, Lizards, Cats and humans all have eyes, but what we see and experience through our eyes is unique to each species. Zaza is colour blind but she sees in the dark six times better than I do. Zaza’s ancestors survived by catching mice at night, in contrast my ancestors survived by picking red cherries amongst green leaves during the day. We think we are in control of our actions and choices, but behind our free will Nature has given us umwelts that behave like guardian angels to guide us to the red fruit which is ripe and ready to be eaten but not the green ones that are harder to see.

Our subjective experiences, the feelings that give us our souls, are hard-wired into our bodies because they are part of Nature’s mechanics of survival. Included in that package are our “guardian angel” umwelts which guide us to instantly recognise both what to do and what not to do. For instance whilst we get feelings of desire and pleasure when we see things that are good for us, a bowl of cherries, we get the opposite feelings of disgust when we came into contact with things that are dangerous to our health, like the smell of rotten meat or poo.

Scientists have divided the perceptual toolkits of most animals into two parts:

- Exteroception (The Big 5 Senses); Seeing, Hearing, Tasting, Smelling and Touching,

- Interoception: (Introspective experiences from our bodies). Feelings of Wellbeing, Pain and our range of Emotional drives. Desire, Pleasure, Fear, Anger and Disgust.

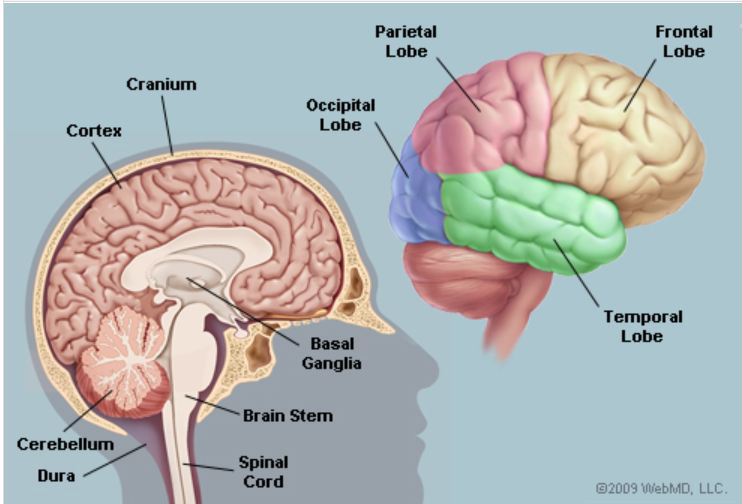

Humans are unique in having put a lot more metabolic energy budget into developing an extra department on top of these perceptual tools. The new area is largely centred in the frontal lobes of the neo cortex (new brain) which is the part with walnut like folds that is wrapped around the basal ganglia that form the core of our brains. In our foreheads at the front end of our neocortex is an area called the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) , sometimes known as the Executive Brain.

In the pre frontal cortex we refine and examine our thoughts with a new kind of consciousness skill set called Metacognition

- Metacognition (the unique human ability to think about thinking). To think about thinking opens us up to see into the minds of others and ourselves. It also means we can view our ourselves in the third person (objectively), as well as in the first person (subjectively).

Metacognition gave us a new ability to view our actions and performance in events objectively, as independent autonomous beings on a time line. This type of cognition is most beautifully expressed in Shakespeare’s wonderful lines from As You Like It

All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts

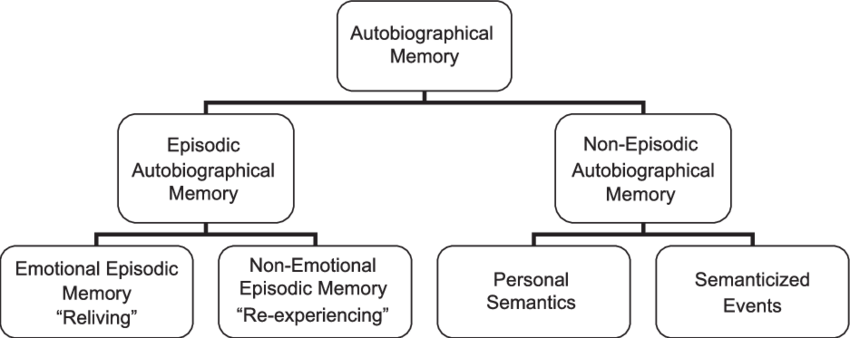

We call this sort of thinking our autobiographical or episodic memory.

Seeing ourselves objectively as a person living amongst other people gave our species the new ability to guess the thoughts behind their behaviours and have enhanced feelings of empathy. This guessing the thoughts of others made us into mind readers and set us up to learn and imitate new social skills from our parents and communities. This in turn led to passing on useful knowledge that built from generation to generation, sharing cultural skills, sharing beliefs and developing languages with story telling traditions.

In humans our Umwelts have extended the boundaries of subjective experience beyond those experienced by other animals. We are mind readers with a wealth of generational shared knowledge, and we perceive our existence as all happening on a time line. These mental insights carry the umwelts of humans to new levels of perception and higher levels of consciousness.

Our subjective experiences are influenced by Belief and Reason, the choice of words in our Languages, the formulas in our Mathematics, Art and Religion, and all of this happens on top of the experiential pleasure in seeing vivid colours, feeling pain and the dampness of leaves under bare feet that we share with other animals.

Metacognition gave our species a new faster way to adapt to new environments. We knew how to predict the seasons, make appropriate clothes, use the habits of other animals to hunt them. With metacognition we invented blue sky thinking, giving us the ability to jump into new habitats without going through the long wasteful, tedious performance of evolution by natural selection, and we came to dominate the world with our flying machines and the fruits of our scientific advancement. Right now it feels as if we are on a roller coaster building weapons of mass destruction we might not have the mental maturity to control and fighting wars with bacteria and viruses. But this is not the purpose of my dissertation. What I am interested in is why do I spend my afternoons with my sketch pad drawing the visitors at Wiseman’s Bridge? What am I doing? Why does it give me pleasure? How will I get better at it? What is it’s worth?

Subjective and Objective

Our perceptive toolkits provide the subjective method through which we perceive what is happening around us. What we see is experienced in the subjective privacy and isolation of our brains. For instance when we human’s look at a dandelion we see plain yellow flowers, but a bees eyes collect data from a broader spectrum of sight which include UV, so in the bee’s subjective inner- world dandelions are seen as having a central blob or landing area.

Everything processed through our umwelt will be experienced subjectively, even a scientist looking at his experiments experiences the science subjectively , but umwelt has a sister Umgebung. Both words were first used in this context by another German Speaker, Jakob von Uexküll (1844 -1944). To give you a feel for what these words mean:

- Umwelt (literal meaning Surround-world) is to perceive of the world as an embodied, subjective experience. ( the world as we as individuals experience it to be). For instance: If I have no eyes I have no umwelt to experience sight and sight; if I am colour blind my umwelt cannot experience the redness of red; if I am tired my umwelt experience hills as steeper; if I am emotionally attracted by a pretty girl my umwelt makes me too besotted to notice she is not interested in me.

- Umgebung ; is to perceive a the world as it is in reality, which is generally interpreted to be as science describes the world to be: At 12OO hours I am looking at a lawn which is 242 square meters large and has 571 flowering daisies plants.

Now that we are loosely familiar with these two words we can begin to divide our world into two elemental forces; Umweltan (subjective perception – the world as we as individuals experience it to be) and Umgebungan (objective and factual – the world as described by science). As we will see the separation of these two elements is a gateway through which we can reach a better understanding of the structural foundations of perception, and of course drawing.

Drawing the Umgebung (The world as it is)

If I were to take photograph of my lawn the camera would probably not record all the 571 daisy plants because some would be would be absorbed into the graininess of the image, others would be obscured by the garden furniture. Nevertheless I could argue that the picture was an accurate record of the real state of the world in my garden. An unedited un-subjective snap shot taken with an iPhone provides impartial factual record of the umgebung of my garden, but it does not record everything about the garden.

Another way to record the umgebung of my garden would be to undertake a field study that mapped every plant on a scaled grid. The plan would again be limited in-so-far as I choose only to record the perennials, and have not included the mosses, lichen, wasps nests and earwigs that were also present. But it would still be a un-subjective factual record of an aspect of the garden, however my record is a partial biased dataset of everything about the garden.

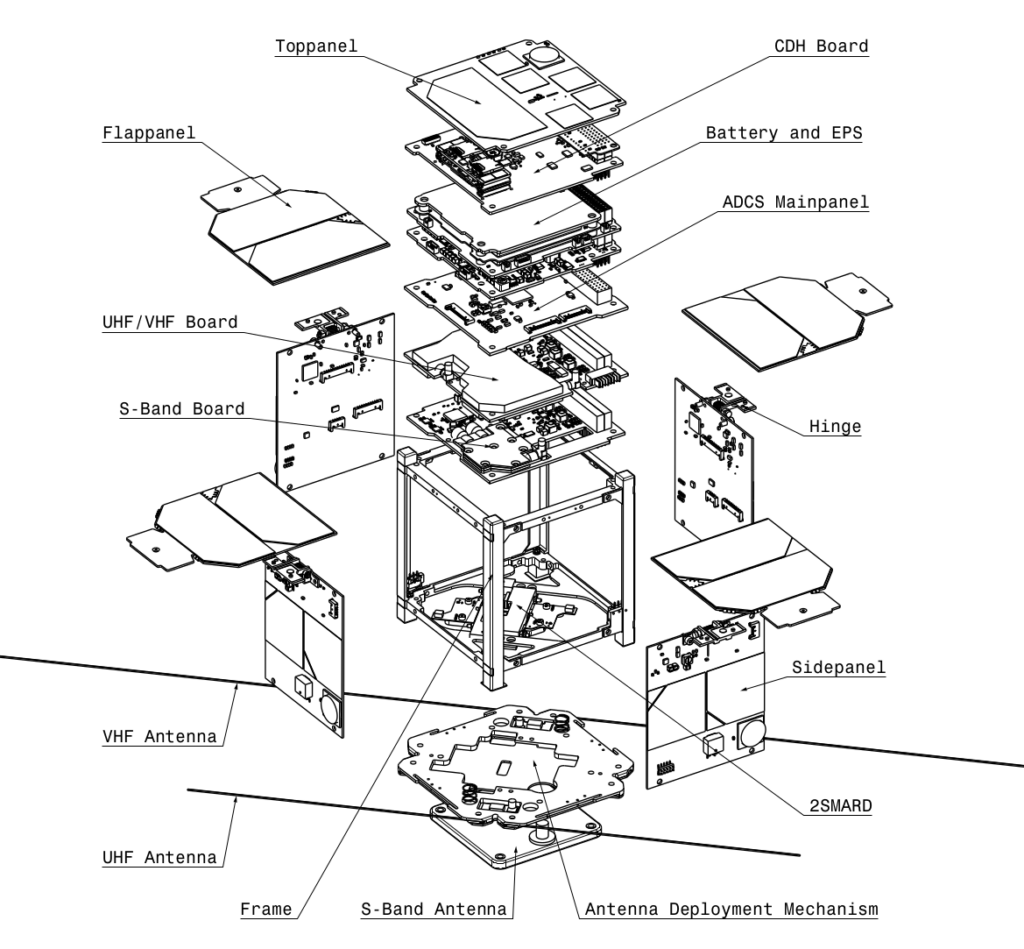

Technical drawings present an umgebungan view of the world, but like the ecologist with his daisies, they filter out noise in the umgebung to present a selective version of the truth.

The information remains accurate about the data found the umgebung, but showing only the information that we wanted to know, making information we want to see clearer to see. The result is a drawing that has filtered the truth to expose more clearly a chosen aspect of the umgebung

Making Models of the Umgebung

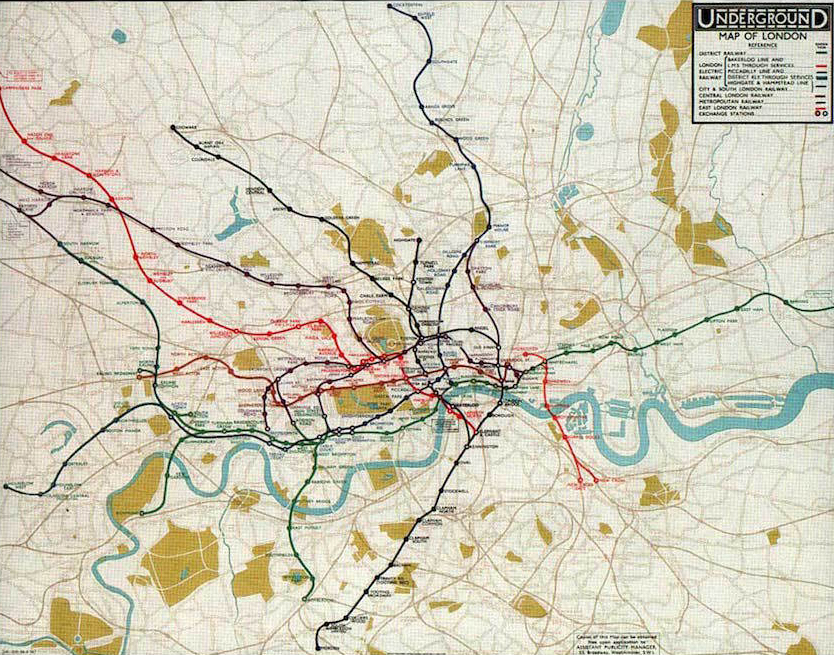

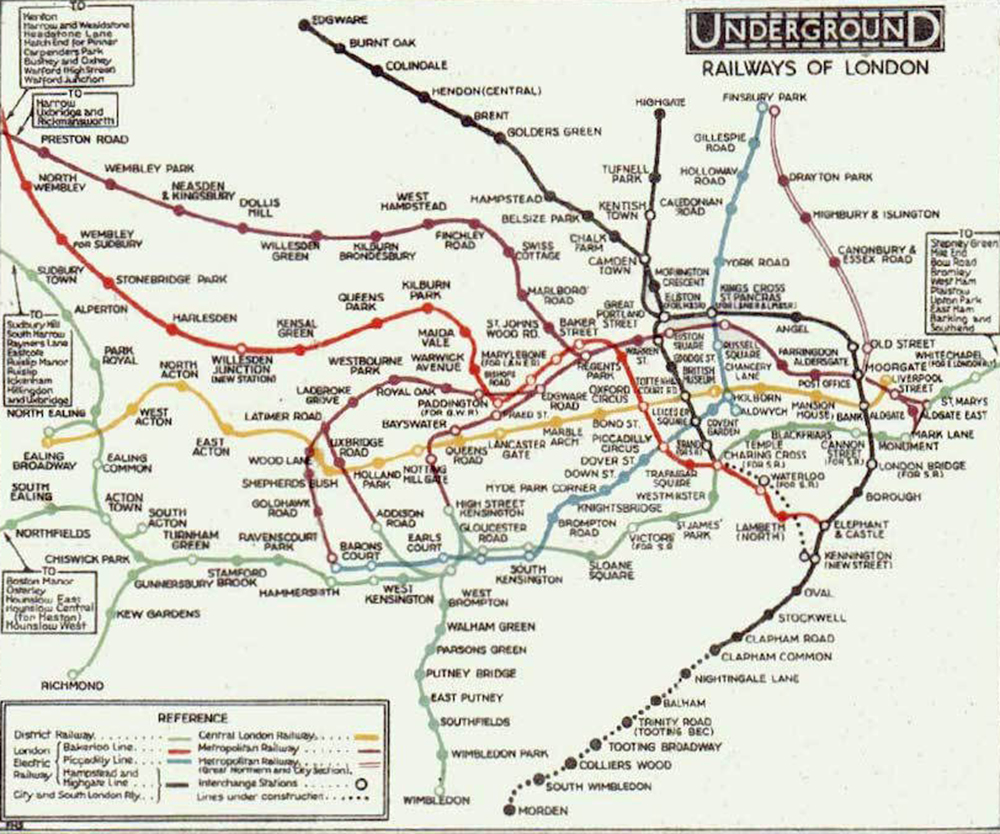

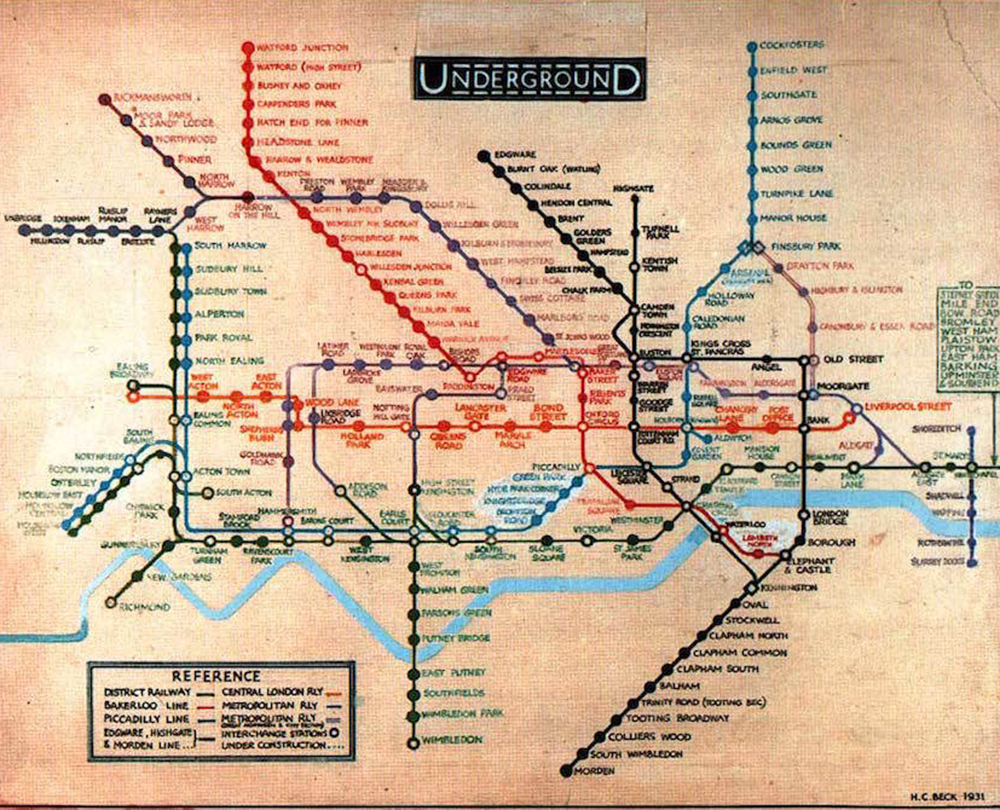

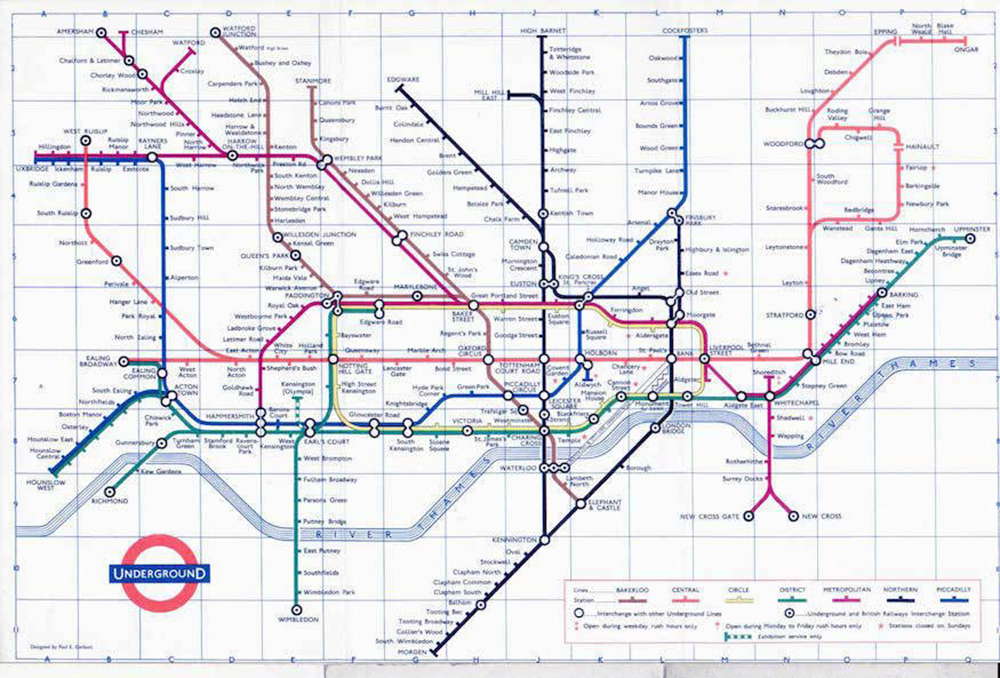

A diagram presents a chosen aspect of things in the world in a stylised way. A good example is the extreme stylisation of selected information on the London Underground maps.

In this series of images we can see how the map was refined in stages, with unwanted information (noise) being dropped as the map evolved.

The final map, created in 1931, is an information chart about how the different train lines interlock with each other. The 1931 Art Deco image no longer looks like a map of London.

For every London commuter the map is as familiar as the words that run through their heads. Travellers with a journey to make drop away from their memories of real stations with real trains, and instead call up an image of coloured lines, imagining their itineries in terms of changing trains where red and blue lines intersect, and then again at the meeting of blue with black. The map is recreated inside our mind as an internal model, part of their phenomenology, that can be visualised like the colour red or a yellow dandelion.

I would like to draw your special attention to way the London Underground map converts all the sensual noise of travelling on the underground into a very simplified abstract idea that can be held in your working memory. It is a dependable and efficient minimalist model of the facts travellers need to accurately follow their itineries.

Internal Models of the Umgebung

Your laptop can crunch data millions of times faster than our brains, but when it comes to learning, predicting and integrating conceptual ideas into solving novel problems they are outperformed by 18 month old infants. Man made computers are very good at making calculations but lousy at doing what our brains do. They are different systems that work on different paradigms.

With the best AI techniques we can program computers to have the “intelligence” to beat our world chess and Go champions, but these skills are learnt by machines that run algorithms and calculations over and over trillions of times for many hours. The super intelligent machines will then perform very well in a very narrow field of expertise, so narrow that changing even the smallest parameter renders them useless. For instance a computer that has learnt to play Go on a 19 X 19 square board will be worse than the stupidest beginner if asked to play on an 18 X 18 square board. Man made computers are inflexible, energy expensive and very slow learners.

The paradigm human Brains run on includes very restricted energy budgets, equivalent of 40 watts. Their leaky wiring and processing speeds are several thousand times slower than silicon chips achieve. However brains are very effective at learning new information, recognising events and cracking problems by applying broad concepts to reach broad generalised conclusions. They do this by creating “internal models” of how the external world works, and using these models to draw conclusions and develop grammars that can be applied across a broad ranges of other applications. The richness of the internal models inside a child’s head are for the most part unconscious and exceeds our imaginations.

It is beyond the scope of this article to make more than a shallow dive, however we do need to understand that our umwelts are much more than the parameters set by our sensory organs. Our eyes pick up redness, but after that the fireworks begin. In a strange self aware state those signals are converted into a subjective experience of redness, the redness of redness. Not only do we enjoy redeness, we apply it inside our models. Redness becomes part of our experiencial history, it

WE meet with some of these models through [erception

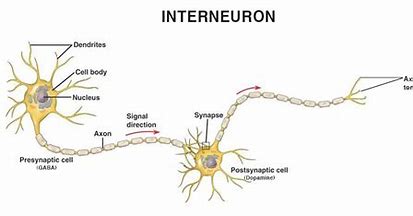

The internal models are stored as patterns that are mapped on to the networks of neurones (brain cells), and perception is measured in terms of the differences between what the internal models predict and what the incoming sensory data from the eyes, ears, mouth skin tell tells it.

The London tube map has been designed to be easily understood by users travelling across the city. It mirrors how the mind works and is a good metaphor for thinking:

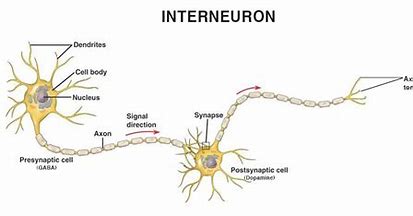

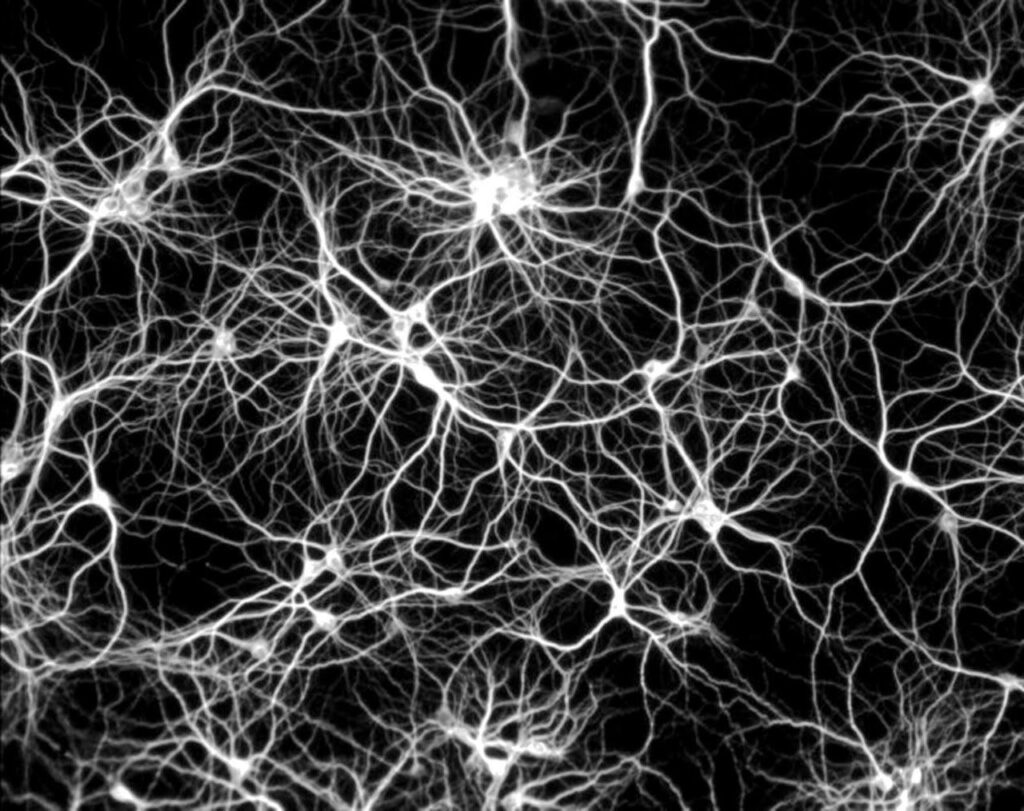

Your brain is an network of about 85 billion string-shaped neurons (brain cells). The tops ends of the neurones have up to 100,000 hair like filaments called dendrites, and these filaments reach out to receptors at the bottom of neighbouring neurones to make connections, creating a network. The process is called arborisation.

The brain crunches patterns, where knowledge of the world is condensed and re-presented in very simplified chunks which are integrated into networks of relationships, recognition on another principle of “the truth made abstract and simple”,

The evolution of the London underground Map is an externalized version of the sorts of things that are probably happening in your subconscious when your brain is learning new tasks. It also illustrates how when we create drawings we make images that have already filtered out much the noise of the world, and how a drawing is an external model that represents the world in abstract relationships and chunks that can be managed by our mental processes, in this case especially with the visual cortexes. The big take home point here is that mind does not process information like a camera does, it reforms and transcribes incoming information into a mind language that is simplified and ready made for adoption by mental processes. The London underground map is so iconic because it managed to bridge the gap between the umgebung and umwelt so well.

Thus the London underground map becomes a metaphor for perception, which whilst seemingly effortless and truthful, has evolved to process the world using lightweight models that can be moved around in chunks and consulted in our working memories to help us make fast accurate decisions without wasting calories.

Until now we have been talking about diagrams, as opposed to umweltan drawings which we come to later. Contrast the two methods of representing the world;

- The camera is unselective data collection. Every square centimetre has the same density of pixels because it is a mechanical process that blanket captures all the data across the grid. It is a energy expensive mirror of light patterns in the umgebung

- The diagram is a partial condensed selection of data from the umgebung with noise removed, and then stylised to make it energy efficient and light for adoption by our brain which works on very low energy budgets.

All thoughts are managed in chunks put into context of other chunks, like the relationship between Piccadilly station on the London Underground map with all the other stations on the map. The mind can also zoom out, and think of the London underground map as a single chunk in another internal models; maybe an internal model about your view of “London” which includes images of Buckingham Palace, the financial trade and theatres . Chunks, relationships an internal models are all part of a single system with which our minds deals with the huge complexities in the umgebung (the world as it is) and converts it into manageable framework that can be comprehended by our umwelts (the world as we experience it to be).

Drawing is one of many ways that internal mechanics of the brain that haqppen in our subconsciousness have been externalised into manual processes that we can have rational control over, for instance;

- Scientists use mathematics as their language to make models of the real world, so they can condense ideas like relativity into abstract formulations like Einstein’s E = mc2 that can be processed in their working memories.

- Language itself is a method of chunking concepts into words and sentences that can afterwards be absorbed and used inside our working memories.

- Drawing diagrams is a language of lines and shapes than make the complexity of the umgebung meaningful in our umweltan world of subjective experience.

Drawing Our Umwelts (The world as we experience it to be).

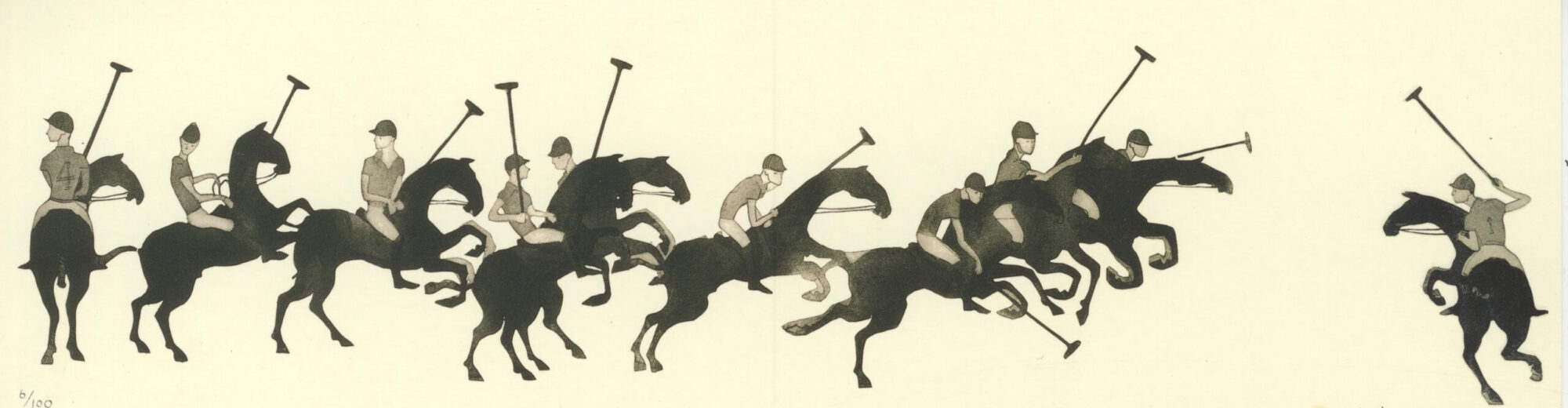

There is a third method, which we could call Art or Umweltan drawing

- The Art Drawing presents subjective experience in a condensed form that can be shared with other minds. A externalised diagram of subjective inner experiences produced through our umweltan processes.

So far we have discussed making a drawing from the perspective of diagrams representing facts about the umgebung. It is a little surprising that it took us straight back to the world of subjective experience, the umwelt. This is a general principle of thought; whenever we look out in the third person (objectively) we end up thinking in the first person (subjectively). Our whole lives are about navigating the world as it is in term of the world as we experience it to be, our umwelts..

Now I want to look at drawing from the opposite point of view: Starting our journey of discovery in our umwelt, in the subjective first person tense, in the world as we experience it to be, and working out towards putting that world back into the umgebung. Manifesting our phenomenology (all that stuff that happens in the privacy of our brains) into the world of things. Making drawings that represent what is going on in our minds.

A photographer will always start off with a factual representation of the umgebung, but the way the image is processed by the photographer can add subjectivity. Here Abbas Baig tells us how he went about transforming a photograph into subjective umweltan artwork.

“Morning Poem. This was a smoggy December morning in New Delhi. In winter, Siberian seagulls flock to the Yamuna River, and I was able to capture this shot of them flying overhead. While editing this photo, I increased the blacks and highlights, and I adjusted the contrast. I also applied the Burn Tool in Photoshop to make a few birds’ wings darker, and I cropped the image to decrease the negative space.” Abbas Baig

Morning Poem by Abbas Baig

Abbas Baig played about with the tones and composition of his photograph to make it closer to the evocative experience he felt when he took the photograph of a boatman on the Yamuna river. He changed the umgebungan information into umweltan information, and by doing so made the image less truthful in the scientific sense, but a more truthful description of his subjective experience. He changed the photograph from being the world as it is into being “the world as he experienced it to be“. As a rule of thumb adding umgebung information orientates the image towards the scientific, and adding umweltan elements pushes it towards the artistic.

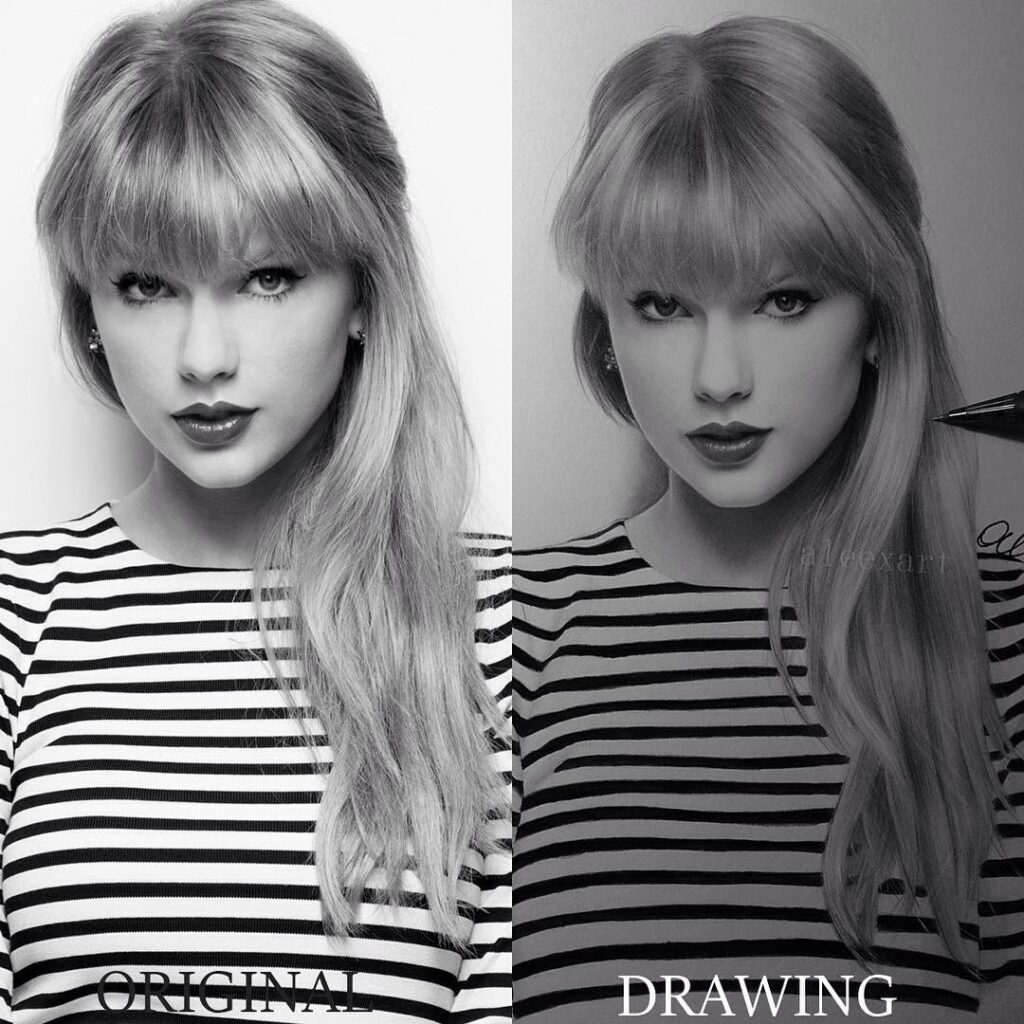

Amongst portrait artists there is a popular movement called photo or hyper-realism. This image of Taylor Swift by Alex Manole is a good example. Many hyper- realists create their drawings by careful mapping from a photograph.

We can love and admire the beauty of Manole’s draughtsmanship, and it would be an interesting picture to live with on the wall, but is the artist really providing any personal subjective input? Unlike Abbas Baig, the object of hyper-realism is to faithfully copy the photograph without introducing your own subjective experience. Hyper-realism goes out of its way to preserve the umgebung recorded in the photograph rather than providing for the artist to participate with his expressive contribution and umweltan experience.

In contrast umweltan drawings are focused on capturing the essence of subjective experience rather than copying objective reality. The caricaturist’s, cartoonists and animators are amongst the people that have been most successful at making the umwelt visual. This image is a portrait of Wellington, known in his day as “the Nose” (a very umweltan nickname). It is a hotchpotch of mental associations, subconscious biases and distortions that have been thrown together and allowed to run wild,. The image looks like nothing we know of in the umgebung, and it nothing like the experience of seeing Wellington if he walked into the room, but it is instantly readable and recognisable because it mimics the mind’s habit of jumping from one associated prejudice to the next. In this sense my use of the word umweltan is correct, even though to a pedant I might seem to be stretching my language.

There is something about this picture that screams “This is Wellington as I experience him to be”. I cannot help feeling that in this picture our strange hidden friend and guardian angel is being exposed to us through some unknowable, unknowable processes.

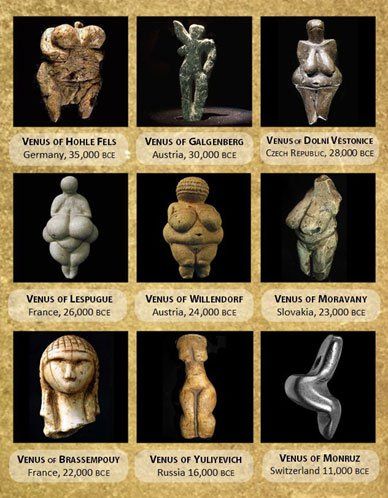

And somehow ART has this power to undress our umwelts and expose them to us. The distortions and melding together of subconscious associations in the portrait of “A Wellington Boot” is reminiscent of the Lion Man of the Hohenstein Stadel (38,000 BC) which is contemporary with the earliest cave paintings and earliest evidence of figurative art ever found. This image of a man’s body with an animals head is a concept that reoccurs in multiple cultures across the world.

Exaggeration is a ubiquitous feature of perception. These Venus Palaeolithic figurines have the typical fingerprint of umweltan exaggeration. They are also metaphorical symbols of fertility, another trait that is silently exaggerated by our guardian angel when we men are looking for suitable partners in marriage.

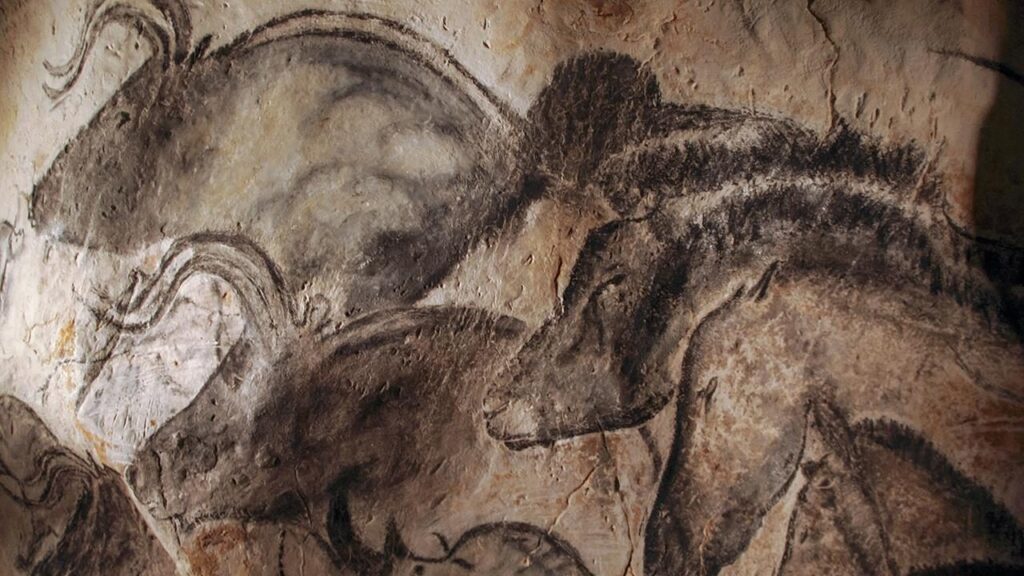

Cave art are the very earliest known paintings. They must have been painted and seen by the flicker of firelight and scholars speculate that they are “representations” of “the spirit world”. Is there anything more subjective that our sense of spirit? Seeing spirit and “belief” in other worlds is specific to the umwelt of our species.

The “representations”, a preferred word to “art works” by some in the Palaeontologist community, is an another interesting choice of words since it is often a preferred word amongst neuroscientists when talking about the creation of virtual images by subconscious processes. Much nearer to our age are the startling the fantasies of scribes in the margins of illuminated medieval manuscripts (marginalia).

You may say that when you look out of your window you will see the umgebung through your umwelt, and there will be no lion headed men or penis trees? Are these not works of the imagination, rather than the umwelt? This is a valid question that requires an answer; The umwelt in our wakeful state is not the same as the umwelt of our dreams and imagination. Whilst I cannot provide evidence to counter your claim, the umwelt images I see when I am awake are perhaps the same but under the stricter supervision than those I experience when I am asleep. Such factors as reason, working memory and knowledge. (Whilst driving late at night I have sometimes experienced hallucinations that bridges across motorways are mountains or castles. It is as if my brain has stopped filtering out wrong options. When this happens I always stop driving and take a nap).

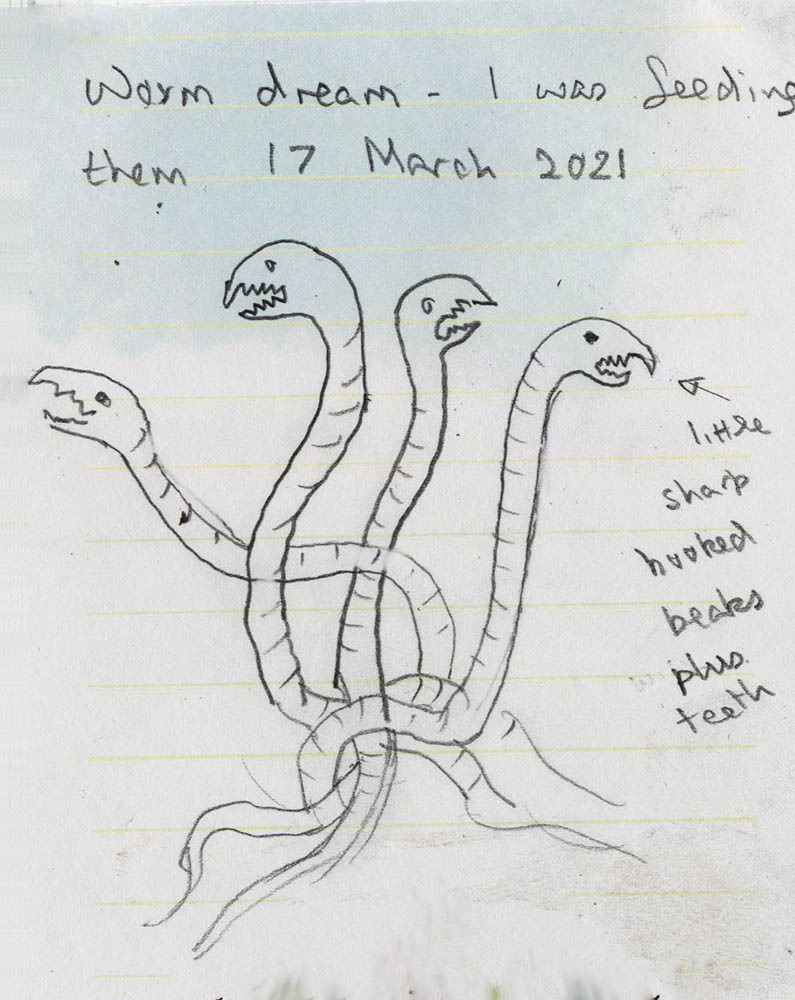

In our sleeping state the umwelt we enter is uninhibited. Only last night I had a dream in which I had a vision of some worms that were asking for food like chicks in a nest. The worms had eyes and sharp vulture-like beaks with teeth. This dream was so vivid that I made a drawing afterwards.

I find it interesting that when I am dreaming I feel no surprise about the images I see. The strange beasties seem to have the quality of normality even though in my wakeful state I would be aghast, even frightened by them.

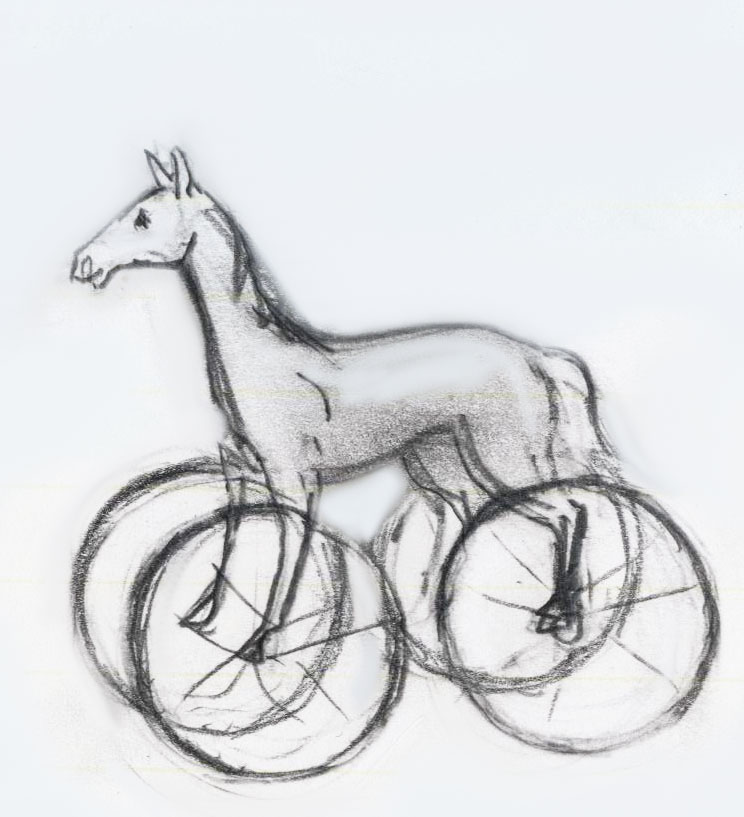

As you go to sleep there is a juncture between wakefulness and sleep where we see hallucinations. It is called Hypnagogia and lasts only a few seconds. I enjoy watching out for this moment because the images that arrive are random, unconnected to my daytime thoughts, vivid and sometimes quite extraordinary. They seem unconnected to the wakeful thoughts I am leaving and unlike dreaming they belong to no narrative; for instance the hallucinations will start an unknown family on motorbike with a father hugging a child (that a few nights ago, where did that come from?), or a house that I have never seen, or a basket of fruit. One night it was a pink horse with large pram wheels that rolled joyfully across my vision.

On anther occasion I saw sheep with trees growing from their backs. Most surprising to me is that the hidden machinery of subconsciousness can so effortlessly generate such a variety of original and perfectly formed ideas. I believe it points to the possibility that underneath consciousness is another bounteous free-flowing world with many complex grammars.

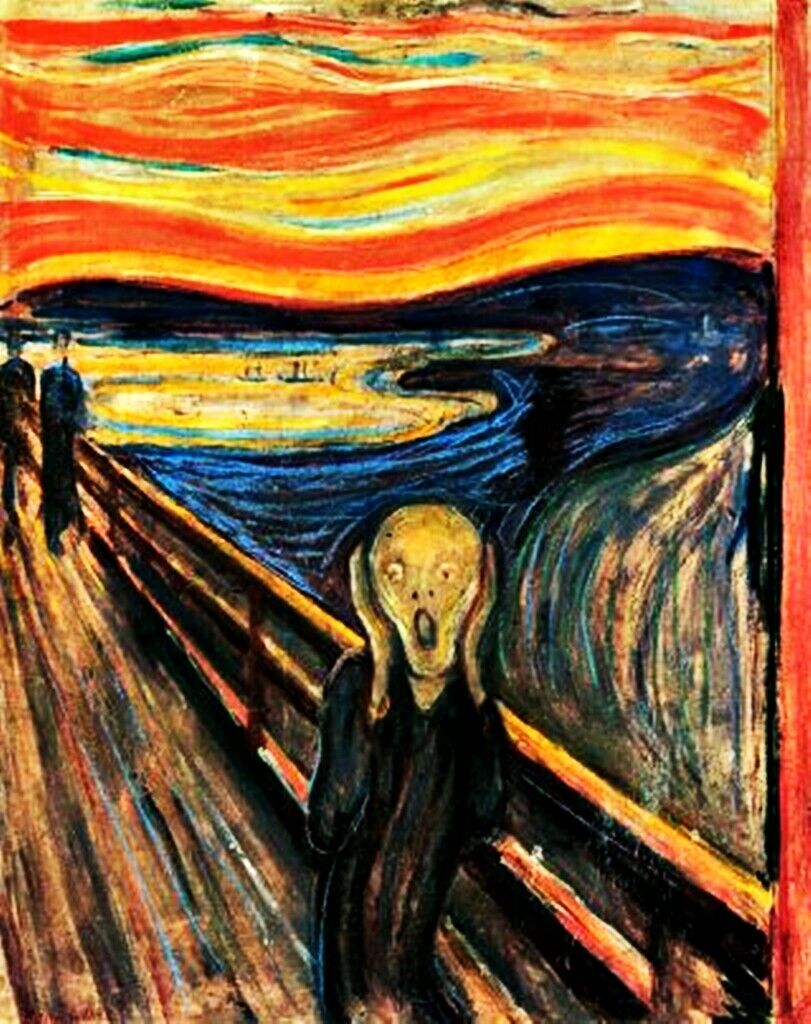

Of course modern painters have used the distortions, exaggerations and metaphor of umwelt experience for inspiration. Amongst the most vivid and uninhibited examples are the works of Edvard Munch who painted his landscapes in primary colours and human faces that look like pears with eyes. In spite of his distortion, and departure from the reality of the umgebung, Munch’s images speak directly to our emotions .

In the ancient classic world a new artistic tradition developed. Artists began to aspire to of reproduce the umgebung so faithfully and in such detail that their art would become “real”. Ovid, in his narrative poem Metamorphoses describes how Pygmalion wanted to bring an ivory statue to life with a kiss.

From the Renaissance until the end of the nineteenth century representational realism was the institutional art of all the great academies of an “enlightened” Europe. It was left to “new” movements of “modern” artists widely called the avant-guard to challenge the notions that copying the umgebung in fine detail was superior to “primitive” art forms. One avant-guard artist, Picasso, after looking at an ethnographic collection of masks declared in surprise modern art is not “modern”.

However hard they tried, representational art was never able to suppress the intrusions and distortions of the umwelt experience. Leonardo Da Vinci, and artists of his generation, spent their whole lives dissecting cadavers in order to develop good enough skills to make their art mimic the reality of the umgebung, but what did the artists do with this new knowledge? They reverted to painting the ghoulish visitations of their worst nightmares.

Umweltan art is irrepressible. It appears to come out of the imagination, which is another way of saying we invent it from nowhere. But our fantasies do come from somewhere; Fantasies of our imagination well up out from a myriad of opaque perception processes that do not obey reason and lie mostly unseen below the horizon of our conscious awareness.

Umwelts are “Truth Memes”

We all have our own way of experiencing the world. As a thought experiment imagine two photo-realist artists making a picture of a dandelion. One artist is a my cat Zaza, the other is Bee, a worker from our local hive. Both artists have been given the task of making an objective picture of the flower they are looking at in the real world.

ZaZa doesn’t really think much of flowers, and her mind wanders, so it is hard work for her to concentrate and do a good job. We have to force her to stick to her task, and after a lot of complaining and scratching she eventually paints a dandelion just as she sees it. To our eyes her picture looks dull because it is made in tones of grey and her lack of interest in her subject matter kinda shows. Nature blessed Zaza with the ability to see in the dark six times better than we humans do, but left her colour blind. Zaza’s main interests in life are catching mice in the night and sex, which is why nature has not gifted her with an umwelt that enjoys the redness of red, or the yellowness of dandelions like we do.

When it comes to Worker Bee’s turn she is really fired up. More than sex, which she gets none of, Bee loves flowers. Bee demands UV paints, and as she paints it seems to our eyes as if Bee is getting it all wrong because her flower has no centre. When Bee flies over our lawn she sees a field of ultra violet landing pads, that stand out like the red of cherries on a fruit tree. It is only when we get out a special camera that photographs UV light that we can see the dandelion like she sees it, and the passion, fine detail and delicacy of her brush strokes.

It is as if Nature gives each species a different truth story. Both Bee and Zaza painted pictures that they thought were true to the world. In Zaza’s umwelt flowers are dull colourless things she hardly notices, in Bee’s world flowers stand out with their golden rings with tasty UV centres. Through natural selection each species have umwelts that exaggerate truths that are useful for their survival.

As the great renaissance astronomer and philosopher Galileo Galilei (1564 1642) put it:

I think that tastes, odors, colours, and so on.... reside in consciousness. Hence if the living creature were removed, all these qualities would be wiped away and annihilated

The umwelts we have are truths, but our truths are no more than a reflection of the way Nature has hard wired our bodies to perceive the umgebung to be.

The Molineux Problem

When a new born baby opens her eyes for the first time what does she see? Is her umwelt already set up and ready to go? Up to now I have written as if sight, with all its vivid colours and 3D forms arrives pre-packaged out of our DNA. I have told you that flowers through the eyes of Bees have UV landing pads, whilst dandelions through our eyes are plain yellow. We see the way Nature set us up to see. In my writing there has been an assumption that Nature has set it up so that when Baby opens her eyes for the first time it is all just there. I have assumed Baby does need to go through a process of learning to see?

If we think about how we learn language. Baby, like all human babies has an innate ability to learn to speak, but she has to go through a learning process before language becomes part of her umwelt . Baby’s first experience of language would be hearing a jumble of unsorted data, a stream of consonants. Baby and Mother are both primed by their DNA to go through a long ritual that starts with Mother making a lot Baby Talk (IDS “Infant Directed Speech”) and helping Baby turn her burbles into words and sentence structures.

When Baby grows up she will see yellow dandelions, but when she first opens her eyes she may just see a jumble of unsorted colours. She may have to learn to understand how to put colours and shapes together, just like she has to learn words and how to construct sentences? The debate around whether we have to learn to see started way back on 7 July 1688 when an Irish hardware merchant called William Molineux wrote a letter to John Locke, the famous English physician and philosopher of the early enlightenment. It is known as “Molineux’s Problem“.

Molineux asked Locke “Suppose a blind man learnt to see a ball through touch. Would such a man, who by miraculous healing was given sight one day, be able to distinguish between a cube and sphere, or would he have to touch the objects first to know which was the ball?”.

Molineux’s problem has been easy to test because people who born blind can be cured later in life with surgery. Oliver Sacks in his book “the man who mistook his wife for a hat” describes the progress of one such patient he calls Virgil. In the first hours and days after his cataracts have been removed, Virgil, and similar patients, cannot distinguish between a cube and a sphere by just looking at it. Only after they have had time to touch the objects do they learn how to recognise and see a sphere.

A large part of our umwelts, like our ability to see colours, are hard wired into our bodies at birth. This means the umwelts of all human beings are broadly the same, but if there is a learning process there will also be a diversity in the way the hardwiring is set up. Furthermore some of us are colour blind, some have perfect pitch, some have super sensitive taste. Hard wiring is not the full story, our brains are constantly being softly re- wired to adapt to the way we have experienced our lives in the world. Identical twins separated at birth will have the same DNA but different biographical histories, and they will granulate their worlds differently, developing divergent abilities that reflect the differences in their education, jobs and the cultural backgrounds. Whilst they will both see dandelions as yellow flowers, in subtle ways they will all experience the world in different and unique ways.

In another study it was discovered that the Occipital lobes, an area at the back of the brain which processes information from the eyes, are smaller in people who are blind from birth. Not only are the visual parts of the brain smaller, but they are also rewired to process touch sensations and language. Our brains are dynamic organs, that is to say when used they grow like exercised muscles do, or shrivel when they are not used enough. Areas that are not being used properly are recolonised to be used for other functions. This property is called plasticity

Learning

Our umweltan perceptions are so much richer experiences than just being able to tell the difference between a sphere and cube. Hard wiring is the biogenetic template on which our ontology of perception is written, and it provides us with an Umwelt we are familiar with;

- colour vision but not UV vision,

- a moderate sense of smell but nothing like as good as a dogs,

- revulsion at the sight and smell of rotting meat and faeces.

- An instinct to learn languages from our parents

- Empathy (including some moral and altruistic behaviours)

- The pleasure of sex

- The pain of being ostracised

- The pleasure of social inclusion

Humans are also uniquely hardwired to have abilities to learn skills from our communities;

- Learning to read and write

- Learning the piano

- Science and rational thought

Until quite recently we thought all the hard wiring took place in childhood, but more modern thinking concludes that the palette of human sensations that underpin human consciousness take a lifetime of practice, learning and wiring for our brains to achieve. We arrive in this world as innocents and whilst we might end them with weaker eyesight and wonky hearing our minds gain in old age richer inner lives and the wisdom of sages.

Much of the important hard wiring is set up in early childhood when we learn to see, hear, taste and walk, but the minds of humans are much more than this. The wiring work never stops being built out. It happen in stages, and the later wiring sits on top of the core structures of the inner brain, and develops in phases that broadly follow the evolution of our species (Phylogenesis). How the soft wiring is laid down is highly influenced by our memories, and are constantly being reorganised and embedded into the hard structure of our brains. Brains are dynamic events performing critical duties, like our heart beats they a fusion of activity and physical being that never rest during entire span of our lifetimes.

Phase 1: Development of basic sensations – As new born babies we know no identity, have no sense of place, no sense of time, no memories and no relationship with the world, but we are not a blank slate, a tabula Rasa, our brains are primed with the architecture but to to learn. Our first sensations are of seeing and hearing the noises of the world come at us in garbled avalanche of sensate experience, out of which the taste of the sweet milk and our mother’s faces gradually materialise. In all the explosion of noise the overloaded brain finds out about the world by looking for patterns, memorising and matching experiences into truth memes; such as the associating of the taste of milk with feelings of being satiated; the cooing sound of “Mama” voice with the pleasurable sensations of being stroked and seeing her face.

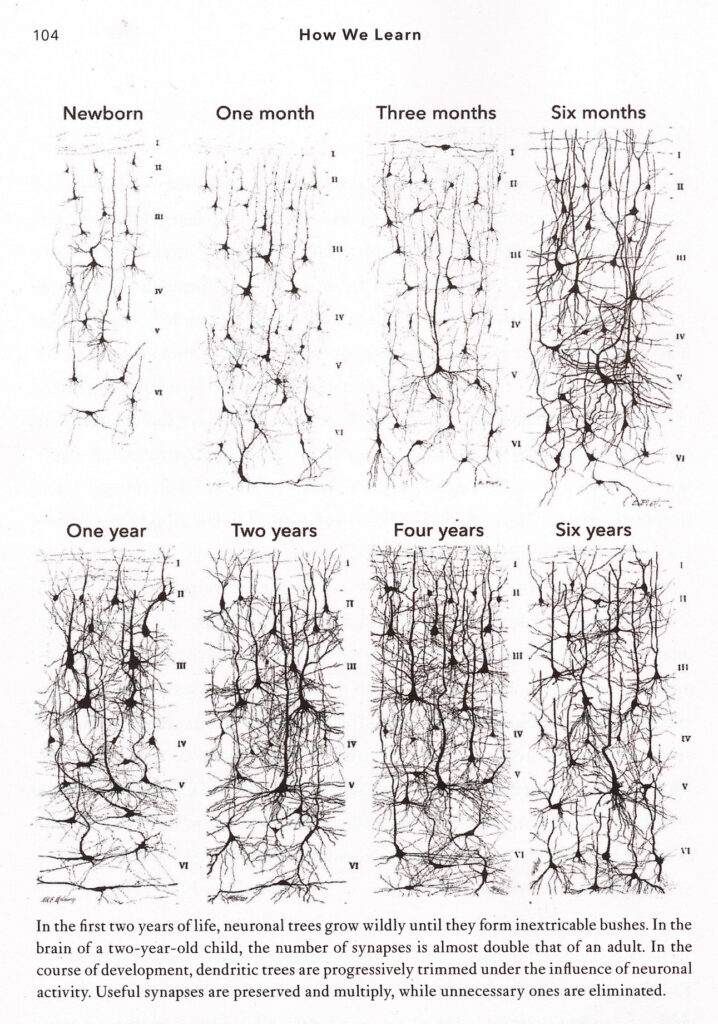

During these first few months and years, whilst the brain is trying to find patterns amongst the garbled cacophony of noise arriving from the outside world, the physical brain is exploding in a process called “arborisation”.

The tops ends of the neurones (brain cells) have up to 100,000 hair like filaments called dendrites, and these filaments reach out to receptors at the bottom of neighbouring neurones to make connections, creating a network. The process is called arborisation.

The networking reflects the rapid expansion of sensory and motor cortices (areas on the surface of the brain) in the first few months of life.

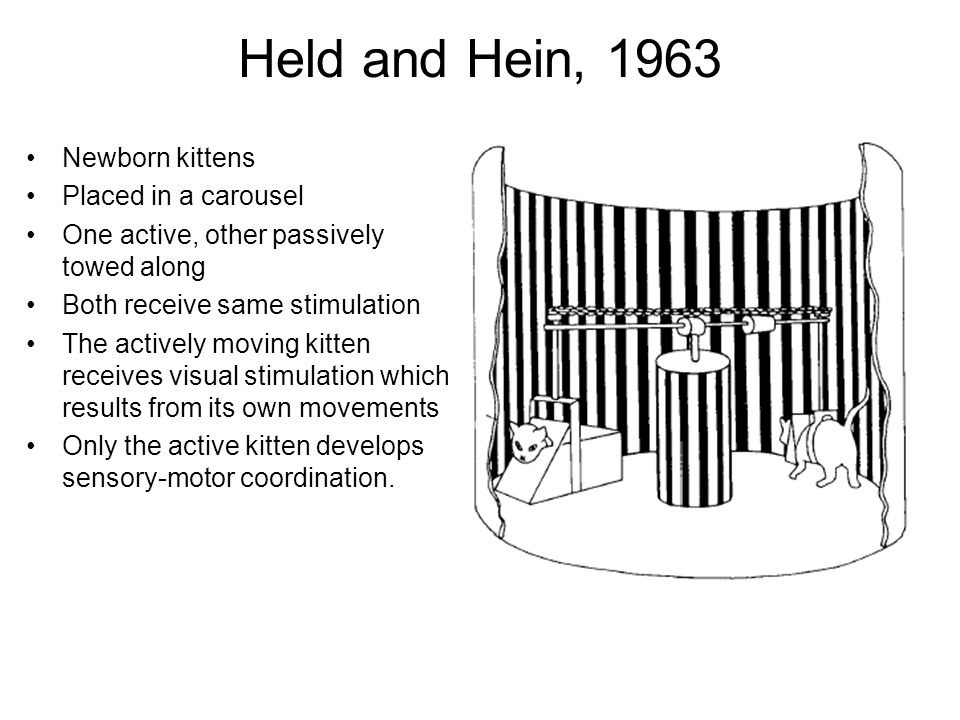

Learning to see is not a single modal sensory experience. Seeing can only be learnt when it is contextualised within the framework of multisensory experiences, as was demonstrated by a cruel experiment with kittens in 1963. Two blind kittens were put in a box harnessed to a lever. One kitten had its feet touching the floor and could walk, the other was confined in a cradle that swung around as its neighbour moved in a circle. The kitten in the cradle remained blind, whilst the kitten that could walk and relate its physical sensations of the world to what its eyes saw developed vision in the normal way.

Phase 2 Pruning: The rapid arborisation of dendritic connections provides a very good landing pad for recognising new sensations, but the young brains are now overconnected. The very young mind of a Chinese child can hear the difference between L and R, but the culture they are born inside does not differentiate the difference.

Their baby brains are over-wired and a new phase of pruning begins where unused connections are removed, creating new truth stories that remove the unwanted noise about the world. A process rather similar to how mapmakers extracted the information about the London Underground into a reality into a simplified truth story that was more readily usable by a 40 watt brain. A young adult Chinese citizen comes out of the process able to clearly hear the words their culture use, but unable to discern the difference between Rice and Lice, or whether Bill Clinton had an election of erection. For the young Chinese adult L and R are the same sound.

Of course pruning limits the brains ability to learn foreign languages, but this is a price worth paying for a brain that works faster and is more energy efficient

Phase 3 Identity and higher consciousness;

Humans are amongst a very small group of animals that have a sense of self identity, and can see themselves as separate not only from the world. This small group of animals are considered to have what is called “higher consciousness”, that is to say they pass the “Mirror test“. To pass the mirror test a blob of rouge is put on the animals forehead, and when they see themselves in a mirror they will try remove it.

very few species have passed the MSR test. Species that have include the great apes (including humans), a single Asiatic elephant, dolphins, orcas, the Eurasian magpie, and the cleaner wrasse. A wide range of species has been reported to fail the test, including several species of monkeys, giant pandas, and sea lions

At 7 months a Baby shows the first signs of understanding she is an-other person, and not part of her mother. A this age babies become anxious about being separated too long from their mothers.

- the reflection is not a another infant

- the mirror mimics all infants own motor movements

- the mirror does not have anyone else behind it

- they are looking at a reflection of themselves

At 18month a baby shows signs of recognising herself in a mirror. This recognition follows a step by step sequence

There is one further step in understanding identity, it is to see the identity of an other. This understanding of an other’s identity is almost uniquely human and called “theory of Mind”.

This video nicely encapsulates the stages of recognition

Phase 4 Memory

The smell of cat urine freaks rats out. It is something that Nature has innately hardwired into the umwelts of rats. Nature hardwires our minds with the wisdom of evolution and natural selection, and provides us with decision making tool kit that protects us from the most obvious and permanent dangers in our environments. But there is only so much that can be hardwired for, and our environments are always changing in subtle ways.

On top of this hard wiring is a system of soft wiring which adapts our umwelts to behaviours that are adaptable to and will take care of more subtle dangers and changes in the environment and dangers. The substrate of soft wiring are experience and memory, and the process is called learning.

If I see a snake in my path my heart stops and I feel fear. If I later discover that the snake was a toy placed there by a naughty child I no longer feel fear, and my umwelt ignores its presence the next time the child tries to frighten me. How we perceive the world to be is guided by experience and our minds are moulded by memories.

Memory scientists divide memory into four types;

- Working Memory; A short term buffer for holding facts and concepts in focus long enough to manipulate, like remembering a new telephone number long enough to write it down

- Episodic Memory; Narrative/Autobiographical memories

- Semantic Memory : Long term memory of general knowledge/facts like dates, names

- Procedural Memory; Autonomic memory of repeated learnt tasks like playing the piano, driving, playing tennis.

If you examine your narrative memories you will discover they have three components; Place, Person and Time.

Where were you on 9/11 = Place, Person & Time

Yesterday I went to London = Time Person Place

We cannot have an autobiographical memory until after we have all three element in place.

- Person – Identity – dependent on concepts of self and other persons

- Place – Organised by special place cells in your hippocampus

- Time – Construction, usually between two place memories

Children develop the third component, time, at the age of three. this is the age at which their autobiographical memories begin.

Our autobiographical memories change our perspective on the world. They allow us to perceive the seasons, the relationships between a unopened bud and and bloom and of course we have a narrative of our lives; I was born in 1953 and went to a convent school at the age of five. Dogs and cats know to expect their dinner at five o clock and walk at 6,00 o clock, but they have no autobiographical memory. They cannot look back on their day and think “I hurt their paw in the morning and then I went to the vet before

I had late dinner”.

An autobiographical memory is a key that unlocks the mind to perceive relationships. A bud will look like a potential blossom and fruit in the autumn after a long hot summer in a few months time. A snowdrop will bring back memories of childhood walk with an old aunt.

A picture of the virgin Mary becomes symbolic of Christian story of a man who died on a cross.

The transition from young to old happens throughout our lives into our old age when our sensate abilities have receded, because our hearing and sight has gone wonky. The umwelt of the young and the umwelt of the old are very different things, and whilst a teenager may experience the world of light and sound more vividly the minds of the old will have acquired ever greater skills of integrating their memories with their experiences of the present. Our umwelts are not static

When the new born baby’s brain is not fully set up when she opens her eyes, touches her mothers nipple and experiences the sweet taste of milk for the first time, her brain has to wire itself up to make sense of the wall of garbled sensate data that is arriving in her brain. The first few years of life

Soft wired Umwelts

In a famous study it was discovered that when London taxi drivers learn the street maps of London their Hippocampus (right side) enlarge. The hippocampi are brain structures shaped like a seahorse that is used for developing and storing of short term memory and spatial/place information.

As we practice new skills the connections between the neurones in our brains are softly reinforced and developed into main highways, and as we experience the faster communications across the brain we “see” things with greater clarity; for instance when a practiced chess player looks at a chess board they recognise patterns and can recall previous games. Their chess pieces project their putative personalities over the threatening formations of their opponents and their imaginations run simulations of how the game might develop.

But a chess player can have off days when their powers seem oddly diminished, maybe followed by days of greater insight. A glass of wine can throw a spanner in the works. It is as if our umwelts are changing as quickly as the weather, and this is indeed exactly what is happening. Our perceptions are as fickle as the memories that come and fade with our mood swings. This is hardly surprising as memories are the substrate of all learning and thought.

Sometimes the simplest experiments have the biggest impact on our thinking. This happened in 1995 when two researchers, Denny Proffitt and Mukul Bhalla, in Charlottesville USA, asked local people in a local park to estimate the incline of a Hill. Almost everyone they asked over-estimated the steepness of the hill. Over several days a typical participant would estimate a 5 degree hill as being 20 degrees.

One day out of the Blue, after a few days of gathering data, they got very different result. The participants on that day began estimating the incline much less steeply. Further research revealed that the visitors to the park that day were mostly members of a soccer team who were accustomed to keeping their bodies super fit by running on average 10 miles a day. These people, with their well tuned bodies, had umwelts that told them a different truth story. They regarded the hill was a lot less steep than the ordinary folk walking their dogs.

To put it simply the steepness of the hill is seen in umweltan (subjective) terms. The hill will look more daunting and steeper if we need to use a high proportion of our energy reserves the walk up the hill. When our bodies are well tuned and fit we have lots of spare energy and the hill looks easy to climb and shallower.

Further research revealed how quickly our truth stories can be changed

- Athletes who were asked to wear a back pack changed their minds and no longer saw the slope as shallow.

- Exhausted Athletes after a run thought hills were 45% steeper than they did before they went for a run.

Our umwelts are changing all the time and are very dynamic!

Partitioned Umwelts.

At the same time that Danny and Murkul asked their participants to estimate the steepness of the hill they had another piece of apparatus to ask a second question. The apparatus was a seesaw which they asked the participants to set to match the steepness of the hill. The same people who verbally estimated a 5 degree hill to be 20 degrees would place the seesaw correctly at 5 degrees. It was as if people have two umwelts telling two different truth stories; one umwelt was connected to their verbal thoughts and measured the hill in terms of walkability. The second umwelt was connected their hands and measured the physical world with complete accuracy.

If you think about it biologically this is very practical. Our umwelts are partitioned to tell truth stories that fit the tasks. When a conscious decision are to be made by verbal/reasoning decision making and thinking areas of our minds the truth stories will include emotional imperatives; “that hill is going to take a lot of energy to climb. The choice is yours, but do you really need to do that?“. When the measurements are fed into autonomic nervous system (ANS), such as about telling our feet where the floor is likely to be as we climb a slope, the umwelt gives us accurate unemotional guidance.

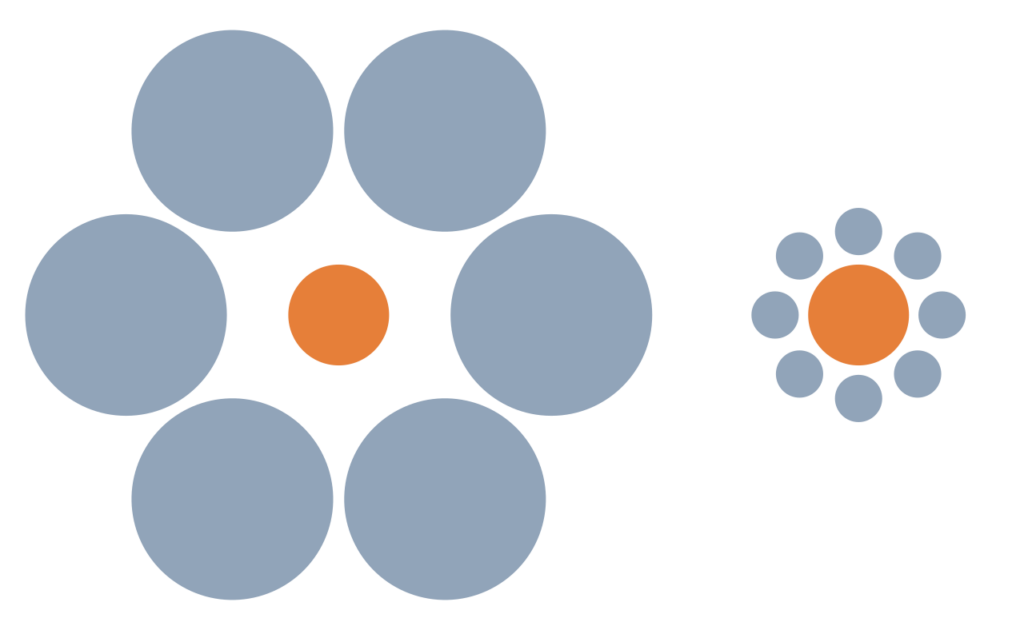

The partitioning of the umwelts for telling different truth stories to different parts of the brain is a ubiquitous feature of our mindscapes, and if looked for can be found everywhere, The practice is most clearly demonstrated by the Ebbinghus illusion. Our eyes are programmed by our umwelts tell our conscious minds that the left orange circle is small and the right one is big, when in fact they are the same size.

If the circles were poker chips on the table your hands would judge their size correctly when you wanted to pick one up, even though in our conscious awareness struth story tells us the left one looks much smaller than the right. This is another example of our umwelts being practical, multi modal perfection instruments that are able to emphasise two different faces of truth at the same time. In one case the important truth is about dividing the chips into bigness and smallness, in the other truth is about physical location.

An Artists Toolkit

Our umwelt tell us truth stories that exaggerate and make bigger the important things in our lives. Whilst much of the substance of our umwelts are fixed at birth by our biological set up, another equally large part is plastic and developed through practiced and learnt behaviour. As we move through the day our umwelts adapt to fit the tasks at hand, and the truth stories the umwelts are telling us are changed to fit with our priorities of the moment. Pain is part of our umwelt, we feel it when we are injured, but the pain miraculously disappears when we need to fight an enemy

Control of the plastic side of our umwelt is often buried deep in the processes of subconscious behaviours and emotions, but we also can have some say over how we partition our umwelts according to how we discipline ourselves and want to view truth. Understanding and owning our umwelts is an important tool in the practiced artists toolbox.

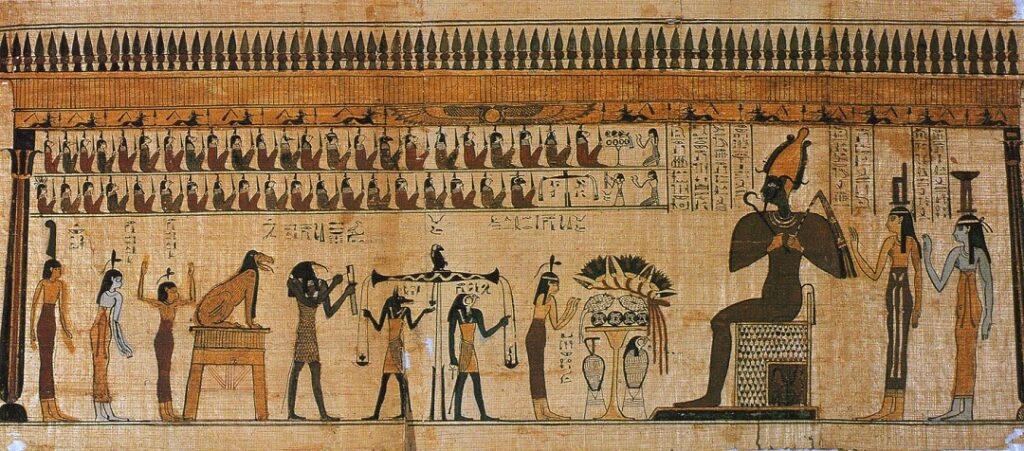

When an important person walks among a crowd we all focus on them, we create a truth story that eradicates the other people in the room and focuses on the one we think is important. Just like the counters in the Ebbinghus Illusion the presence of important people loom larger over the ordinary people in the crowd. The Artists of ancient Egypt noticed this in their umwelts, and would emphasise the importance of the Pharaoh by making him larger than his subjects.

As artist we employ truth stories the truth stories our umwelts present us with, but as we have already understood a shallow hill can look steep when we are tired. A small counter surrounded by bigger counters will look smaller, except to our hands which measure it as being the right size. Our umwelts change as quickly as the focus of our thoughts and our moods. They know no constancy. The artist is dipping into a pool of ever changing truths.

For Scientists truth is a rigid thing deduced and loved for its constancy. For artists seek the plasticity of truth experienced and felt with our umwelts. It is a fickle thing that changes with context, as when see hills that get steeper because we are tired and n longer have the energy to climb them, or people who loom large in our worlds because they have special importance in our lives, or girls who look more beautiful because they are our partners in making a family.

Each one of us is part scientist part artist. Every decision we make is guided by our emotions and reason not always working together. We all live in a multiverse of truths that compete for our attention I will leave last word to Emily Dickinson

I Died for Beauty

I died for beauty, but was scarce

Adjusted in the tomb,

When one who died for truth was lain

In an adjoining room.

He questioned softly why I failed?

“For beauty,” I replied.

“And I for truth—the two are one;

We brethren are,” he said.

And so, as kinsmen met a-night,

We talked between the rooms,

Until the moss had reached our lips,

And covered up our names.